This CBC News article (plus, I'll admit, its comments section full of the usual right-wing ignoramuses) is what's grinding my gears this morning:

Like a boogeyman to scare children, stagflation is rolled out every now and again by economic prognosticators to warn of how awful things can get if we're bad. Perhaps that's why many economists don't seem to be taking the threat seriously.

Similar to the response after warnings of inflation in 2020, most financial commentators have been saying that the threat of stagflation — an unusual combination of a stagnant economy and steady inflation — is small.

But U.S. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell did not seem as confident this week as he has been in the past.

"I think we have a good chance to restore price stability without a recession, without, you know, a severe downturn," Powell told a news conference on Wednesday.

"No one thinks it's easy, no one thinks it's straightforward, but there is certainly a plausible path … to do that."

Powell made it clear that getting inflation under control was the priority, praising his predecessor Paul Volcker, who finally slew the inflation dragon, with interest rates of nearly 20 per cent that drove the 1980s economy deep into recession.

While we're currently far below those levels, Powell pushed rates up half a percentage point, saying he expected the next two moves would also be half-point increases.

But there are some who fear the current U.S. central banker has waited too long to hike rates, allowing rising prices to get a foothold and making recession inevitable, even as North America faces surging imported inflation.

A number of prominent U.S. commentators, including former U.S. treasury secretary Larry Summers and economist Mohamed El-Erian, have been warning that rate hikes, while too late to stop people from expecting persistent inflation, could themselves nudge the U.S., Canada and the world into recession — and into stagflation.

...

According to the guidance of the Phillips curve, which some say was out of whack even before the pandemic, inflation and economic strength (as measured by job creation) rise together.

But in 1965, Iain Macleod, the British Conservative politician who coined the term, was among those who noticed the Keynesian rule of thumb wasn't working.

"We now have the worst of both worlds; not just inflation on the one side or stagnation on the other, but both of them together," Macleod is recorded as saying in the British House of Commons, where he was finance critic.

"We have a sort of 'stagflation' situation," he said. "And history, in modern terms, is indeed being made."

As with many ideas in economics, there is a lot of argument over the whys and wherefores. But when stagflation swept the U.S. and Canada in the 1970s, blame was cast on the supply shock brought on when OPEC members suddenly demanded an increased price for their oil, pushing already-high inflation even higher and simultaneously battered the economy.

"When I was a graduate student, all the professors would say, 'Oh, we'll never see this era again of letting the inflation genie out of the bottle,'" economist Constance Smith, a professor emeritus at the University of Alberta, said wryly.

Like others who lived through that time, she remembers it as being "unpleasant" — a term echoed exactly by Powell from his own memories, as repeated attempts by central banks to quash inflation failed to convinced people that prices would stop rising.

...

Instead of an OPEC-driven oil price hike, we now have the Russian invasion of Ukraine driving up the price of energy and food, continued supply-chain distortions from the pandemic's earlier waves and, most recently, the shutdown of Chinese cities, as Beijing tries to coral an outbreak of the Omicron variant.

Those forces are likely to continue to push prices — and inflationary expectations — higher, even as American and Canadian central bankers hike rates to try to smother domestic demand.

On Friday, when Canada's latest jobs numbers come out, economists predict employment will continue to surge, exacerbating the worker shortage and helping to drive up wages.

As Powell noted, strong employment and healthy savings mean the economy can survive the required destruction in demand. Another way to say it, is that it has a long way to fall.

With so many forces pushing prices higher, even as he channels Paul Volcker, the world's most powerful central banker made it clear he knows that bringing the North American economy to a soft landing — one without a sharp downturn and free from stagflation — will be difficult.

"It's been a series of inflationary shocks that are really different from anything people have seen in 40 years," said Powell. "And it's obviously going to be very challenging."

"Stagflation." The paradox of inflation and a moribund economy both occurring at the same time. According to J. M. Keynes inflation was a product of an overheated economy and could not occur in a depressed one. Or so Keynes' thought is described. I'm not so certain that if you went through all of his writings you wouldn't find him unable to think of a time when the economy was in the shitter but prices were soaring.

I'm right now reading an art history book about the life and times of the Venetian painter Titian. Early in his career Venice was at war with a number of adversaries. As a beseiged trading nation Venice's economy was interrupted. It's mainland agricultural areas were either occupied by foreign troops or pillaged. The city was flooded with refugees without resources or employment. Which (to state the obvious) meant high unemployment. And with war-time shortages, of course there was inflation.

My point being that while "stagflation" is rare it is not something mysterious, caused by who knows what.

I thank the article for telling me about Ian Macleod. I read a lot about the history of postwar economics and the "War on Inflation" back in the 1990s and early-2000's, and I'd never known that it was a British Conservative MP who'd coined the term "stagflation."

But there is little else that I found valuable in this article.

First of all, had there been other inflationary times in the 20th Century before the 1965-1980 period? Yes. There had been a lot of inflationary pressures in World War Two. But at that time, government policy-makers had been informed by their understanding of the inflationary pressures of World War One. Wars often make some people rich. With the growth of the idea of "Total War" in industrialized societies, some wars could make many people wealthy and millions more financially comfortable. In World War One for instance, a lot of impoverished British industrial workers knew economic security for the first time in their lives. Robert Roberts' The Classic Slum: Salford Life in the First Quarter of the Century (an account of his boyhood in the northern industrial town of Salford, England, along with the political-economic/cultural forces that influenced it) describes the WWI as the first "good times" his community had ever known.

Of course there had been inflation. But there were trade unions in England (and the USA and Canada and other industrial nations) at the time. And WWI was remarkable for the way that these trade unions were able to win wage increases for their memberships to resist the erosion in their real purchasing power. Employers in WWI were aghast because previously, as capitalists in capitalist societies, they were able to use the state to serve their interests, including the subduing of worker movements that challenged them. In WWI though, it was Total War. All the resources of the nation-state had to be mobilized in the struggle and the politicians were responsible for the military as well as the economic, cultural and poltical situation. In the context of Total War it was clear that giving the workers what they wanted (and paying for it later somehow) was the most efficient way to keep the artillery shells and uniforms and helmets and machine tools pouring out of the factories. The capitalists were told (for the first time in probably 100 years) that, no, their selfishness and arrogance were NOT the most important things in the world, so shut-the-fuck-up and give your workers the money they need to buy food and get back to work.

(You also have to imagine how the inflation of the times, combined with subsequent pay increases, wiped-out the debts that many poorer people were burdened with. Just as people with low-incomes find a $500 emergency to be unmanageable and a $2,000 debt to be a long-term burden, whereas a middle-class or higher person would find those numbers easily manageable, the tiny debts of the industrial working class evaporated between 1914 and 1918.)

Which is not to say that things were wonderful. Workers were going on strike because war inflation was constantly eating into their household budgeting. The currency was being devalued and government debt was rising. (Again: "Worry about that later. Right now there's a war to win.")

It was that experience that informed the governments in 1939-1945.

Of course there had been inflation after 1918. The German hyperinflation of 1921-23 was caused by being the losing side in a war that Germany had financed by borrowing. German leaders had expected to win the war and force their defeated opponents to pay for its costs. Being defeated complicated things. Reparations payments were at first difficult and then onerous and then impossible which led to the French occupation of the industrial Ruhr Valley. Germany's leaders ordered what amounted to a general strike in the Ruhr to protest the occupation and paid the Ruhr's idle citizens with paper currency that soon became worthless.

Again: Nothing mysterious. No magic. Political-Economic circumstances caused inflation.

This was understood in WWII. Massive spending on weapons, fuel, the upgrading of factories, as well as shortages of labour on farms and in factories from the loss of men to the military, and the diversion from consumer goods to war materials would produce inflation. Obviously millions of people earning a steady paycheque doing war work but having no consumer goods to buy (you could only make yourself buy so many war-bonds) would also produce inflation. The governments of all the belligerent nations (well, at least the Anglo-American ones) created price control boards to nip it all in the bud.

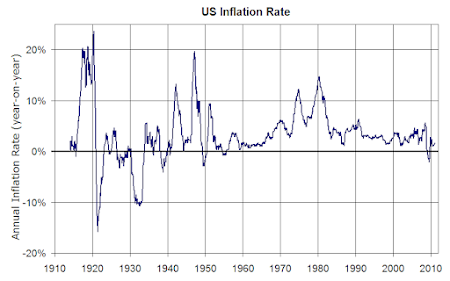

Obviously there were shortfalls between intention and delivery. Obviously there were grumblings. But inflation was much less of a problem in WWII than it had been in the previous conflict. You can see it all (for the USA example) in the graph below:

Notice the uptick in the late-1930's to 1941, when the war started in Europe and the US economy began the slow process of putting productive facilities that had been mothballed during the Great Depression back into working order. Then note the stark decline in the inflation rate after 1941 when the price control system was implemented. Notice as well the soaring inflation after 1946 when price controls were removed. Some of that was no doubt due to the release of pent-up demand for consumer goods and housing. And I'm pretty sure that increases in productivity helped reduce that inflation soon afterwards. The smaller uptick in the early-1950's was the Korean War and NSC-68.

Look at how high US defense spending was during the 1960's! That's when the bulk of the nuclear weapons infrastructure was being constructed. Also, the Vietnam War was being fought at the time. Notice the decline after 1968. As good as it is for the USA to wind-down war spending, a temporary result of any such decline is going to be a fall in employment in those areas. The same goes for the reduction of the armed forces.

The next thing that I want to talk about is "Inflationary Expectations." All of us who grant credit to the architects of the post-1945 economic order (capitalism's "Golden Age") understand that it was an unprecedented period of general prosperity and stability. What capitalism tends to deliver is "Boom & Bust." This is the stuff the CBC article is mentioning. The Phillips Curve describes the typical trade-off between Employment and Inflation under capitalism:

When people are secure and they have money in their pockets they tend to spend it. (Especially since the mid-20th Century when advertising and marketing became huge industries manipulating people into buying stuff they didn't need so that the capitalists could sell their production.) The more people spend the more capitalists produce. Higher sales equal higher revenues equal corporate growth.Capitalist firms tend to have to show growth to shareholders. Before Keynesianism what tended to happen in a growth area of the economy was for competitors to flood in and increase production and therefore supply. If lots of people enter an industry the people who supply things to that industry have more demand for their products. So they increase their prices. Workers are enticed to work for the new firms leading to increased wage costs. What is often called a "boom" or a "bubble" is created. (This also happens in the capital markets. A growth industry attracts investors who pour money in seeking fast and large returns. If more entrants continue to come into the industry the competition for financing will increase driving up the costs of financing for all players. The increased supply of the product created by the industry lowers the price of that product decreasing profits. Often times prices would plummet, profits would evaporate, firms would fail, workers would be fired, loans would be defaulted upon, etc., etc. If the industry was large enough and important enough the resultant business and financial collapse would cause a nationwide recession.

Keynesian economic theory arose out of the 1930's Great Depression, which was itself the product of the inflationary boom in the late-1920's Wall Street stock-market. Keynes (and other economists like Joan Robinson) advocated using government fiscal policy (taxing and spending) to control this boom and bust cycle. When an economy was "over-heating" (boom-times) the government should increase taxes before things got out of hand. This would increase government revenues for any inevitable downturns when the government should cut taxes and increase spending. Fiscal stimulation and restraint, applied before busts or booms built up any momentum, would keep the economy on an even keel and prevent economic catastrophes that produced massive human misery and people like Hitler who took advantage of that.

Obviously, "free-market" ideologues like Ludwing Von Mises, Frederick Hayek and Milton Friedman, bristled at this. Capitalists responded to Keynesian tax increases as someone taking the punch bowl away just as the party was getting started. Whatever the case, policy makers tended to err on the side of economic growth over moderating the business cycle. For over two decades people were confidant of being employed, over getting pay increases, or growing markets and profits. Inflation was kept manageable for a decade or so but it was always there. By the late-1960's everybody (still confident in their ability to have their way) was factoring inflation into all their plans.

With the 1971 "Nixon Shock" and the 1973 OPEC "Oil Shock" things went right off the rails. Pierre Trudeau's government imposed wage and price controls after having mocked the idea in the recent election. Then the 1979 Iranian Revolution threatened yet another oil shock and everyone grabbed oil wherever they could. But Paul Volcker got the genius idea to raise the prime lending rate to 20% and destroyed the economy.

That's it for today. I'll finish this in another post(s?).

No comments:

Post a Comment